5 Comments

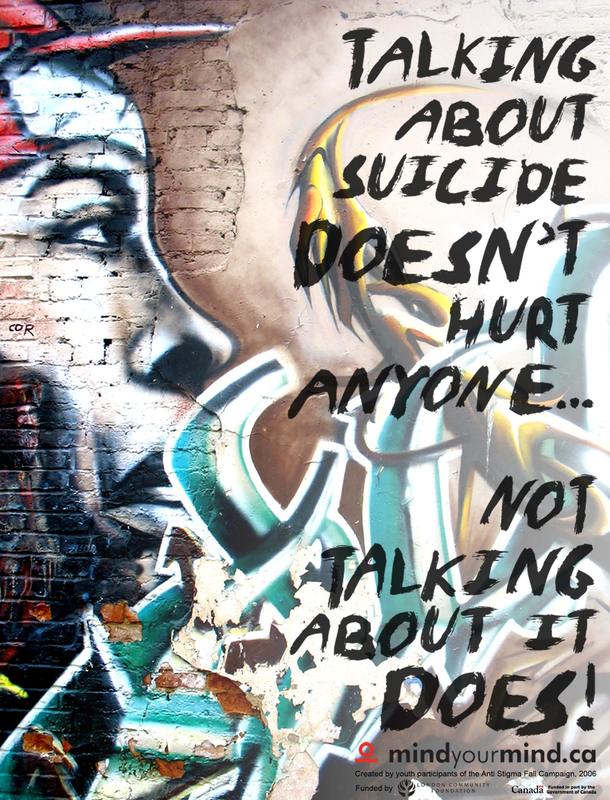

Shame is a soul-eating emotion Carl Jung Until my husband died of suicide, I believed it was something that happened to others. I naively presumed that it could not happen to me; in my family. My only brush with suicide was news reports in the media and a dear friend in school whose parent had died of suicide. Even then as a young girl, it struck me that my friend’s family refused to discuss it. It was cloaked in an iron curtain. I sensed there was something shameful about suicide. Ironically, when faced with the suicide of my spouse, I too was overcome by the same sense of shame. What would I tell the family? What would I tell my friends? Would they judge my husband as a criminal? Would they judge me as having failed in my wifely duties to prevent this? I began to evolve a strategy of the official version of his death (prolonged illness, sudden death, whatever is acceptable) and the real version (death by suicide). I decided to use either of the two versions, depending on who I was talking to. Today, when I look back, I realize that like most survivors of suicide loss and survivors of suicide attempts, I too was experiencing the stigma associated with suicide. How did I ‘catch’ this? Dominant narratives of suicide locate it in a context of crime and sin. In Medieval Europe, for instance, people who died of suicide were denied burial and their families were ex communicated and their property confiscated. While societal attitudes towards suicide, and survivors of suicide loss are no longer so blatant, the tradition of stigmatization nevertheless persists in several subtle and not-so-subtle forms. There is no social acceptability associated with suicide, which is viewed as a character or moral flaw. A stigma, is a mark of disgrace. It is something to be ashamed about or feel shameful about. Stigma is located within a larger social context that tends to view a particular issue, for example, suicide, mental illness and people impacted by it in negative ways. This is known as social stigma. And simultaneously, people impacted by suicide tend to internalize the feelings of shame, blame and judgment, known as self-stigma. Social stigma perpetuates negative attitudes and stereotypes about suicide that are internalized by all people as a default setting. Hence for all survivors of suicide loss, the knee jerk response is shame and self-blame. It is common for people to blame the victim or the family, not realizing that the causes that drive a person to suicide are multiple and “lie with the forces of suicide itself in the same way that people of die of other illnesses.” We wouldn’t blame a person or the family when the cause of death is non-suicidal, why then do we indulge in blame games and accusations when it comes to suicide: “Didn’t you see it coming?” “Were there any clues?” Negative attitudes can be conveyed through a combination of several pathways: Gossip, relentless speculation, intrusive probing, negative media portrayals, insensitivity, social isolation, naming and blaming of suicide victims and their families. Or worse, there is the “wall of silence” around suicide that makes it clear that it is a social and cultural taboo and therefore not to be talked about openly; but stashed away as a “secret.” Such speculations adversely impact and exacerbate the trauma of survivors of suicide loss. They compound our primary loss and makes the grief complex and complicated. The social stigma of suicide leads to self-stigma that is associated with low self-worth, guilt, shame and self-blame, which influence our grief trajectories and well-being. Like a mold festering in darkness, the stigma, shame, secrecy and silence around suicide proliferate in the darkness of ignorance, fear and negative stereotypes. Writer Maggie White perceptively sums up the symbiosis between shame and stigma thus: “Self-stigma is the birthplace of shame. And shame and stigma have been doing a destructive, cyclical dance for long.” The relationship between stigma and shame of suicide is the classic chicken and egg conundrum. Which came first? However, that’s beside the point. Suicide is a preventable public health problem. It cuts across demographic barriers and no one is immune to it. We need to mainstream empowering conversations on suicide anchored in compassion, concern and care. It takes a convergence of diverse stakeholders to break the barriers and collective wall of silence around suicide and build bridges of support and connection. Preventing suicide is everybody’s business. Every voice matters…

Last year, as a then recently bereaved survivor of suicide loss, I directly experienced people’s insensitivity and judgmentality regarding suicide, the suicide victim and of course, survivors of suicide loss. That was an epiphanic moment for me. For, I then realized the heavy smog of stigma, and shame that shrouds suicide. This, along with the culture of shame and silence that prevents people from viewing the issue with compassion and sensitivity. Naturally, blame, judgment, isolation and exclusion is the dominant narrative of suicide. However, for every person who eroded my faith in humanity, there were a handful who restored my faith in the essential goodness of people. Among them are my dear friends and former colleagues, Dr. Synthia Mary Mathew, Dr. Carolyn Nesbai and Dr. Roopa Ravi, Department of Psychology, Lady Doak College, Madurai. Synthia, Carolyn, Roopa and I had been out of touch for several years. But that did not stand in their way they heard about my husband’s tragic death by suicide. All three of them came to condole me. Their behavior was a stark contrast to most people who had condoled me. None of the three asked me any intrusive questions. No gossip; no speculations. No inquisitive questions such as:

On the other hand, their loving gentle presence was reassuring and comforting. They created the space and permission for me to talk. They listened with empathy and concern. I did not sense even an iota of judgement in them. Neither did I sense blame. In fact, they bolstered my resolve to SPEAK about suicide and create spaces for informed conversations on suicide. It is a matter of great ride for me that the first awareness programme on suicide prevention launched by SPEAK was inaugurated at Lady Doak College last month. And the first gatekeeper training in suicide prevention is also being launched here on September 10—World Suicide Prevention Day. So, does one need to have a background in psychology to do what Synthia, Carolyn and Roopa did? Certainly not. All it takes is that one needs to be a good human being who reaches out unconditionally with love, compassion and sensitivity when someone is in distress. More so if it’s a survivor of suicide loss. Big Hugs Carolyn, Synthia and Roopa for compassion and sensitivity in action! Suicide Prevention needs to be anchored in a context of compassion and concern; not blame and judgment. Let’s work together to break barriers and build bridges!  For the person you lost, the pain is over. Now is the time to start healing yours. A Handbook for Survivors of Suicide by Jeffrey Jackson I discovered the term survivor of suicide loss only when I lost my husband to suicide last year. Until then, death by suicide was something that happened to others. It happened in other families. Not in mine. People who died of suicide were faceless, nameless statistics. However, all these defenses crumbled when I had to confront the staggering reality of my loss. A survivor of suicide loss is someone who has lost a person dear to them to suicide. A close family member, a dear friend, colleague or a health care professional (notably mental health professional) could at any point be a survivor of suicide loss. “You are a “survivor of suicide,” and as that unwelcome designation implies, your survival—your emotional survival—will depend on how well you learn to cope with your tragedy. The bad news: Surviving this will be the second worst experience,” writes Jeffrey Jackson, a survivor of suicide loss, in AHandbook for Survivors of Suicide. Suicide, as we all know, is an intentional self-inflicted death. Edwin Shneidman, the pioneering suicidologist, vividly describes suicide as “psych ache” or intense psychological pain. Not surprisingly, mental health issues have been identified as a predisposing factor in 90 percent of deaths by suicide. According to the American Association of Suicidology[1], “the primary goal of a suicide is not to end life, but to end pain.” The statistics are indeed grim.

Death and the resulting emotion grief—the loss of someone we love—are universal experiences. However, a death by suicide, has been described as a death like no other. Suicide, like death by accidents, murder (homicide) and even unanticipated sudden death, is another form of traumatic death. However, death by suicide doesnot elicit the same level of compassion and empathy in people to support the bereavement process. This huge empathy deficit makes a survivor of suicide loss feel isolated and excluded. The American Psychiatry Association (APA), suicide bereavement as “catastrophic” on par with a concentration camp experience. According to the APA, family members of individuals who die by suicide—including parents, children, and siblings—are at increased risk of suicide—almost 400 times higher than others. Survivors of suicide loss are invisible and marginalised. They often encounter blame, judgment or social exclusion, while mourners of loved ones who have died from terminal illness, accident, old age or other kinds of deaths usually receive sympathy and compassion. Thus, grief and the grieving process for survivors of suicide loss is complex and complicated. It is compounded by negative societal attitudes based on stigma, shame, secrecy and silence around suicide. This is because we tend to view suicide through a morality lens rather than a public health crisis and mental health issue, which it truly is. “It’s strange how we would never blame a family member for a loved one’s cancer or Alzheimer’s, but society continues to cast a shadow on a loved one’s suicide,” writes Deborah Serani in Understanding survivors of suicide loss[2]. There is a strong sense of shame associated with suicide. Most survivors of suicide loss prefer not talk about suicide; of someone who died by suicide. We are deeply ashamed to admit this. Instead we tend to create “acceptable” explanations of the cause of death that we choose to tell others. If a loved one dies of suicide and someone asks us about the cause of death, we often tend to say, “It was a heart attack” or some other “natural” cause of death that is socially acceptable. We do not seek to glorify suicide; nor do we condemn it. People who die of suicide are not heroes; nor cowards; nor criminals. Suicide is nota crime. It is public health crisis. It is a mental health issue that is treatable and preventable. Such informed perspectives can change conversations on suicide and also ensure supportive spaces for survivors of suicide loss to rebuild their lives. [1]https://www.suicidology.org/ [2]https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/two.../understanding-survivors-suicide-loss\ |

Dr. Nandini MuraliDr. Nandini Murali is a feminist and a gender and diversity professional. She is an author who also provides technical support in communications for the social sector. When she is not working, she heads off to the forests with her camera. Currently, she has a magnificent obsession with photographing leopards! Archives

October 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed